Introduction

As well as archiving sources for the future, part of the work of the DIAMM project is to attempt to restore and retrieve lost works using the already sophisticated and still developing technology available through digital photography.

Only a few pre-reformation British music manuscripts survive in even semi-complete form. Most are damaged and fragmentary, and have been preserved only because they were re-used as binding material or for other purposes: this music went out of fashion quite fast (a testimony to the vitality of the tradition: few manuscripts contained music more than 30 or 40 years old) and when obsolete many manuscripts were consigned to the book-binders waste-box (or, in one case, for use as backing for some ceiling paintings at New College, Oxford). Medieval vandalism was compounded by the more wilful destruction at the Reformation and again in later centuries when books were re-bound and the early bindings containing the music fragments simply discarded. This practice was common up to the mid/late 19th century; there is a notable difference in fragment survival rates between libraries that rebound extensively in the 19th century and those that did not.

Restoration process

More information regarding techniques employed in virtual restoration may be found in the DIAMM publication: Image Restoration Workbook.

The use of digital images to explore the possibilities of restoration in a virtual environment (i.e. without intervention in the primary source) has been a possibility for some time, though mainstream image processing software has only recently reached a level of sophistication coupled with cost-effectiveness for the processes to become practically available to a wide user-base. The aim of the DIAMM project in developing restoration techniques is to use public domain software that many potential users of the techniques may already own, and others could afford to buy.

There are a number of image-processing applications currently available, but the most widely-used is Adobe Photoshop. The advantage of mainstream software like this is that it is commercially economic for the developers to continue to upgrade and improve the product, and the cost of obtaining it will remain within a range accessible to a high percentage of potential users. Because of its wide customer-base many of the functions available in Photoshop are designed towards a creative graphical end, irrelevant to virtual restoration (VR). However, three tools are of specific value in VR (layers, levels and selective colour), with a host of smaller routines offering additional subtlety.

Photoshop allows any process applied to the original image to be added as a Layer. This superimposes the alteration in much the same way as placing a succession of transparent overlays which can be added or removed. This is far more than simply a sophisticated undo feature. As well as being able to switch the visibility of an overlay on and off, it is possible to adjust its opacity and also the manner in which it affects the underlying material. Sequential overlays can be shuffled to achieve optimum results, grouped and masked in complex ways. Once an ideal finish is achieved the overlays can be permanently flattened onto the original image, and the result saved alongside the untouched original as a TIFF or other format file. The unflattened photoshop file is saved as a reference and record of the processes applied.

Because of the marked variation in restoration needs across even single leaves, one particular overlay may improve one section of a document while disimproving another section, and the interactive fluidity of adding, removing, masking and adjusting layers can become an essential part of the process that cannot be discarded. Photoshop allows an image to be saved (in its proprietary format) with the layers intact, so that users can continue to switch visibility of layers on and off or adjust their opacity. This is an extremely powerful feature, but has the disadvantage that resulting files can become very large, depending on the number of layers being saved. Individual layers can be merged into each other, which can save some space.

Layers can be imported from other documents and superimposed in the same way as layers created internally: ultra-violet images when overlaid on a faded original have proved illuminating, and in a similar way, performing multiple major alterations to a document, saving it separately and re-introducing the altered image as a semi-transparent layer to the original has produced unexpectedly good results.

Level Adjust is probably the most basic tool offered by Photoshop, and has yielded more impressive results than a whole host of sophisticated filters. Brightness and Contrast adjustments are available and can sometimes be sufficient for sources which are simply badly faded. Level adjust is a more subtle approach to the same problems. The level adjust tool offers a histogram which graphically represents the wavelengths of the colours present in the image. Peaks and troughs indicate colour density:

By adjusting levels, either in colour-specific channels, or all channels together, it is possible to spread a narrow colour range over a much wider bandwidth, thus darkening the deeper and lightening the paler colours. Most often, adjusting the full RGB spectrum is the most useful primary approach, revealing colour shifts that are too subtle to be seen in the original image. By performing Level Adjust actions within an added layer, the results can not only be switched on and off, but can also be re-adjusted at a later stage, a feature not available when level adjustment is applied directly to the background image.

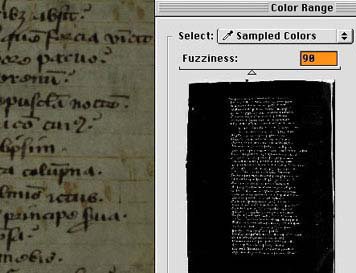

Photoshop's Colour Range selection tool (from the Select menu) enables the user to select pixels of a specific colour and also to capture pixels of a similar colour range. Using the pointer to indicate the colour pixels to be selected, the degree of similarity can be specified by the user as value from 1 to 200: the selected area appears as a negative white in the preview box. The selected colour can then be replaced by a pattern fill based on the background of the leaf, a neutral background tone, or it can be darkened or lightened using level adjustment.

This has proved the most important tool in 'lifting' layers of dirt, glue or later over-writing from a document, by selecting a specific colour, mounting that selection as a layer and applying level adjust to the specific colour areas selected. The process nearly always has to be repeated several times, and the colours selected with increasing accuracy by enlarging the image repeatedly to a point where the pixels begin to break up. Repeating the process with limited selections avoids any colour range extending to material that you wish to remain unaffected.

The same process is used to darken writing that has become too pale to read using select colour the colours of the note-shapes in this example were isolated, and then darkened by using level adjust in a layer.

The example left/above removed overwriting from a palimpsest document and then darkened the music that had been scraped off, but was still just visible. As the aim was readability of the underlying material the results are more dramatic than would be expected with the majority of documents. Where readability is more important than an attractive finish, the ability to separate and manipulate colour channels is a useful tool and serves to emphasize how much hidden information there is in high-resoultion images that the naked eye cannot perceive.

There is always an ethical problem in applying this process:

Some Projects using image processing technology are generally looking for repeatable algorhithms that can be applied to a group of sources. The nature of the medieval documents in the DIAMM collection means that no single process can be applied to all the sources with equally satisfactory results. Even repeating the same operations on a single page can produce startlingly different results.

More detailed and complex restoration processes are possible using image-processing software, but these are not discussed here. In general, an ability to look beyond the primary purpose of a piece of software and explore new processes is essential in digital restoration, since no one process, or group of processes, can be used on every source. Once familiar with the software and comfortable with the concepts behind digital restoration processes, most scholars can achieve satisfactory results.

Restoration samples

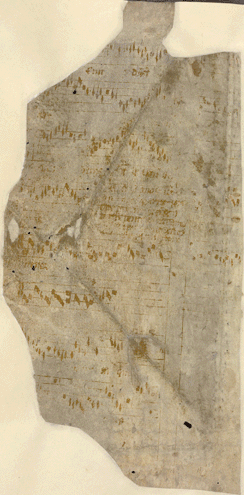

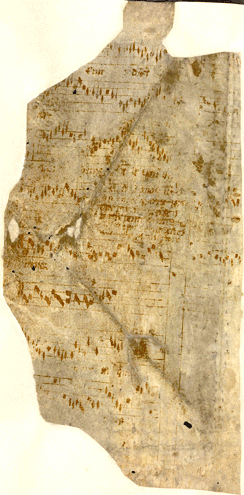

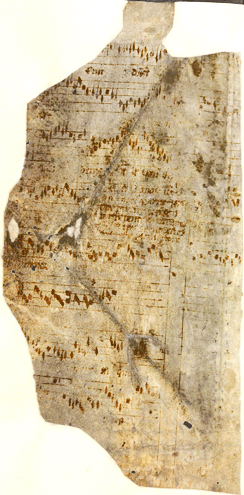

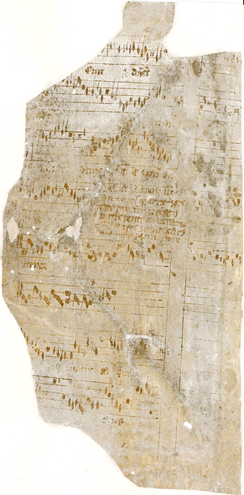

Palimpsest (Oxford, Corpus Christi College MS 144)

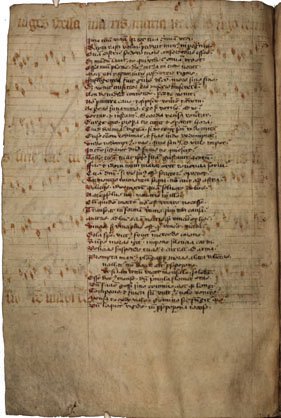

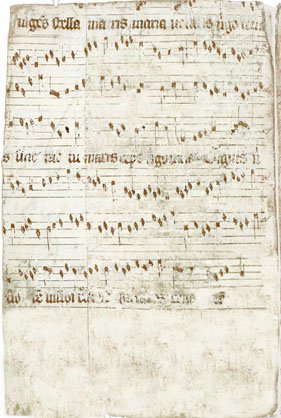

Corpus manuscript 144 is unusual (though not unique) in containing leaves from a 14th-century music book that were scraped, refinished and re-used for writing another text in the 15th century (the Libermetricus de nova poetria of Geoffrey of Vinsauf). The music leaves were also trimmed, removing still more of the original musical text. First discovered in the 1970s, the music in this manuscript has until now been virtually illegible: it is clearly present, but a continuous composition could not be transcribed. The following pictures show a folio of Corpus MS 144 before and after recovery undertaken by DIAMM. Description of the process is given below in Process.

The images on this page have been provided for viewing only by kind permission of the President and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Oxford: please do not download or reproduce them.

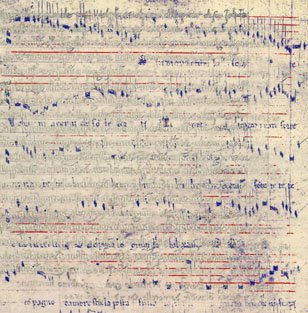

The images show a much reduced version of a digital image that was captured at high resolution using conventional daylight balanced lighting: the first image shows how the page looks to the naked eye without the aid of ultra-violet light. The underlying music is barely apparent, and that overlaid by text is unreadable. The second image is of the same page after digital restoration. In between is an animation that shows the gradual transformation of the document.

The first stage of enhancement involves the removal of the overlaid text. This is done in several stages, and the text is replaced in this case by a neutral background colour. Once this is done, the contrast level is slightly altered to darken the underlying music and lighten the background. The next stage was reached by lightening the background colour, heightening the contrast between the ink colour that should be retained and the colour of the parchment which can be discarded. However, because the ink has faded or is there is very little of it left, in places its colour is almost inseparable from the background.

Compared to an undamaged source this is still not very easy to read, however there is enough information now for someone familiar with the style of notation of the period to read every note on the page.

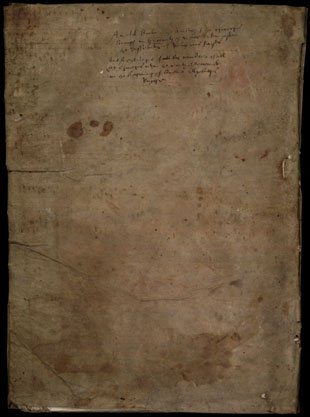

Dirt Removal (Stratford, Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, DR 37 Vol. 41, back cover)

The commonest form of ‘damage found in medieval fragments is the simple accretion of dirt. Since parchment was much tougher than paper it was often used as reinforcement for binding or to form binding or a wrapper itself. The Stratford source is a fascinating case study: a large vellum leaf from a music manuscript (or loose-leaf collection) was reused as a wrapper for paper documents. For many years it was believed that there was either no music written on this face of the leaf, or that if there was it was permanently lost. Inside the wrapper the leaf is remarkably clean and clear and the music is in extremely good condition.

The images below have been provided for viewing only, by kind permission of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, and may not be reproduced without permission of the Trust.

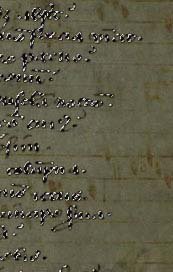

In this case a similar process was applied to the Corpus fragment, though here there was negligible overwriting to exclude. However the dirt accumulation on the surface was very dark, and apparently obscured any notes that may have appeared. On the top left corner there were some shapes that appeared to be notes when the image was magnified, and the colours of these artefacts were searched across the image and darkened, while areas that were clearly background were lightened. The result is far from beautiful but again is now fully transcribable, not just the notes, but the text too (not visible at this small size).

It is evident though from this source that even the most basic restoration techniques requires editorial decisions: the restorer had to decide which colours were notes, and which were background. On the original image a string of rising minims was visible in the middle of the top half of the page. On restoration these minims disappeared, and turned out to have been in the gap between two staves. Evidently a different decision on which elements to darken and which to lighten would have produced a quite different result: it is believed that this line of ascending notes must be an offset from another leaf, now lost, and a second restoration process must be undertaken to attempt to recover some of the lost offset.

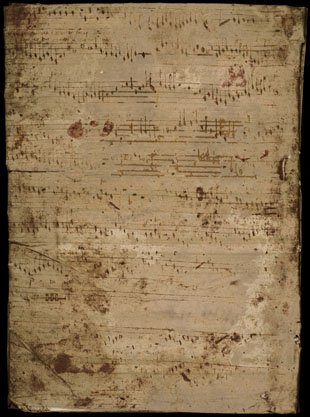

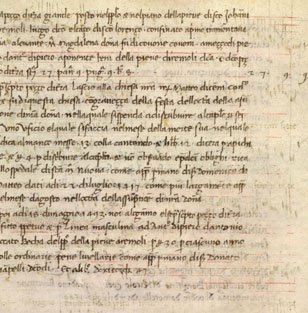

Palimpsest repair and editorial process (Florence, San Lorenzo, MS 2211, f. 82v)

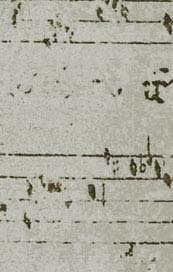

The main problem with the type of restoration shown above is that the appearance of the original source is ‘falsified by the restoration process. It is possible to come to the restored image and see the naturalistic colours which would imply this is the condition of the original source. In presenting digital restoration it is actually much more profitable, rather than darkening existing colours, to replace a ‘found colour with a completely unlikely colour, such as green, blue or purple. The effect is very dramatic: not only are the notes extremely clearly readable, but there is no question in the mind of the viewer that this is a restored image, as it cannot be natural. In addition, the areas of colour selected by the editor/restorer are clearly apparent, enabling later users to make some evaluation of the accuracy of the restorers work. It has been found that this type of restoration, using bright colours, yields more readable results than other processes with a more ‘natural finished appearance.

The two images here are from a major palimpsest manuscript source in Florence. The music manuscript was completely scraped and refinished, often to the extent that all that remains on a leaf are the very edges of the music. Some pages however are better, and what can be seen once the overwriting is removed is eminently transcribable, particularly as it is now known that many of the works have concordances in other sources which can act as a check against the found music in San Lorenzo 2211.

These images are provided for viewing only by kind permission of the Chapter of San Lorenzo, Florence. Please do not copy or reproduce them without permission.

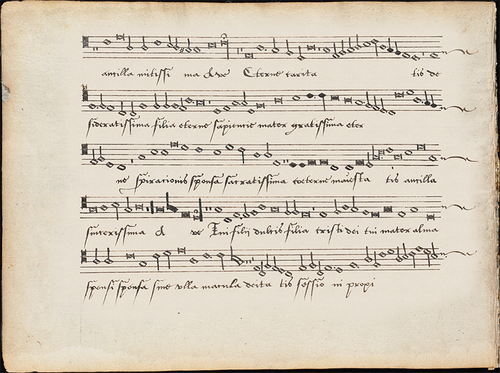

Digital Reconstruction after acid damage (Oxford, Bodleian Library Mus.e.1–5)

Recent digital recovery work involved the reconstruction of a set of 16th-century partbooks damaged by acid burn-through and lacing. 700 images were reconstructed by a team of in-house experts and external volunteers to return these books -- effectively lost to scholarship and use -- to readability and publish them in colour so that they could be used as they had been intended.

In order to remove the acid show-through pattern fills were constructed using undamaged areas of the page. The fill was then 'painted' over the showthrough. Part of the process was automated globally, using colour selects based on the rust-coloured showthrough, but most of the fine detail had to be drawn manually, either retrieving material that had been removed by the automated process, or extending the selection to refine the automated fills. Some of the images took as much as 20-25 hours of work. As well as the original images, negative Photostats taken nearly a century ago were used where the acid damage was less advanced to reveal some pen strokes lost in the modern digital images. Close to the end of the project a small number of infra-red images were made where heavy burn had hidden notes but not cause complete disintegration. Only damage caused by the aciditity of the ink was repaired, so scribal emendations and other artefacts such as water stains were retained.

The images below are provided for viewing only by kind permission of the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford. Please do not copy or reproduce them without permission. If you would like to know more about this process please contact the project. The full set of images will be published in partbook form by DIAMM Publications in 2019.